Subscribe here to receive Project Person each Friday morning.

Meet Kitti Murray // Project Person #11

What project are you currently working on? A memoir-ish project involving my poetry and prose, along with excerpts from my husband’s journals and letters.

What are some of your other projects? Founder of Refuge Coffee Co.

(Note: I usually read and record these emails for those that like to listen, but unfortunately I just can’t make it through this one without crying. I tried! -Callie)

We named him Chief when he became a grandfather, which was an immense relief to me—the daughter-in-law. William or Mr. Murray was much too formal, especially beside his wife’s spirited Kitti.

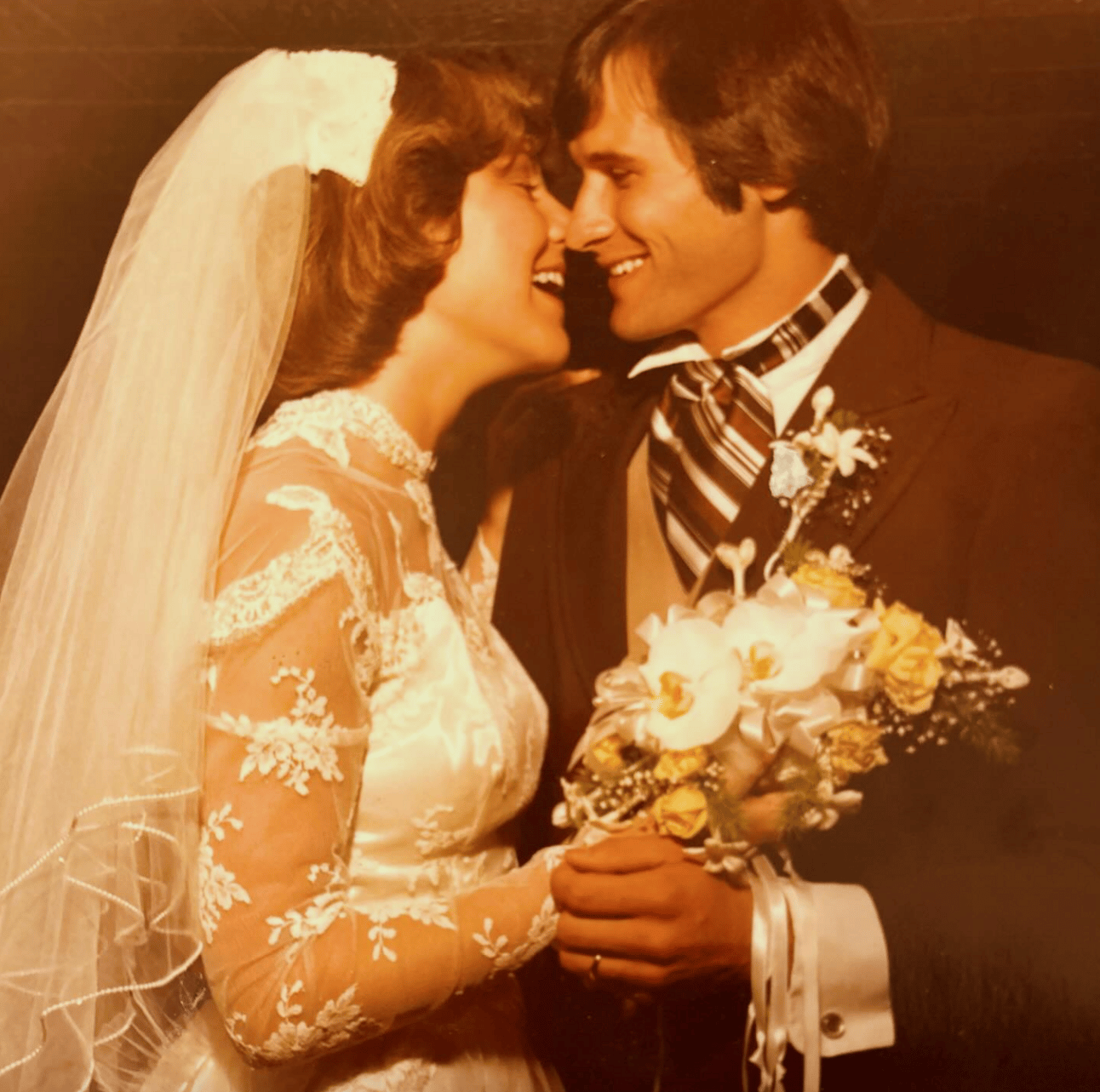

I met him when I was just seventeen and on my first date with his son, David. In between dinner and the bowling alley, David brought me to meet his mom and dad, bucking stereotypical family patterns from the beginning. Here the teenage son was proud of his parents; later his wife would be fond of her in-laws.

…Thus begins something I wrote just after my father-in-law, Chief, passed away last year.

We each carried our own trauma and grief from his death, and at some point I needed to rearrange the words I was feeling into something coherent on a page. Months later, I shared the Google Doc with my mother-in-law Kitti. It felt selfish to claim my own grief, but it also felt cathartic. Writing my experience helped me understand; letting someone read it helped me feel understood.

And there was no one who would understand like Kitti. Of course she shared in this grief, although her own was immeasurable. (Mine was just a hint.) But Kitti also shared in the “medicine of writing”, as she called it.

Kitti has always been a writer. It was her dream in middle school (a poet as a career!), her major in college (a double major in English and German), and her financial contribution to the family as her boys were growing up.

When I first started dating her son David, she had just published her first book—on parenting prodigals, of all things. I remember reading the story of Middle School David’s big stint in the slammer after shoplifting a Stone Cold Steve Austin t-shirt from Upton’s. (What a way to character-check a new boyfriend! Just read his mother’s book…)

Kitti’s friend Ben called her some time after she published A Long Way Off and said something along the lines of, “I read your book. You can write. Can you come write for me?” He had a production company and began to hire Kitti for projects, which eventually led to “collaborations”—or what’s often known as ghost-writing. She collaborated on dozens of books, even getting to travel to Cambodia to research one. I still can’t wrap my mind around the complexities of this type of writing—of understanding someone’s story so fully that you could write an entire book from their point-of-view.

At some point, she and Chief wrote an outline for another book she considered publishing under her own name. This Mortal Marriage, they called it.

Chief had been diagnosed with a lymphatic cancer called Hodgkin’s Disease when he was 22, just months after they had gotten engaged. He endured a brutal bout of radiation that destroyed the cancer but also did considerable damage to his body; he suffered a massive heart attack at 38 because of radiation’s effect on his arteries. Numerous cardiac procedures marked the decades that followed, and Kitti and Chief were consistently made aware that their marriage—their lives—were gifts.

They never pursued publishing This Mortal Marriage, but not for lack of care; they just had so many other things they cared about, too! They had become grandparents a number of times over, and they had moved to a town called Clarkston, deemed by TIME Magazine as “the most diverse square mile in the country.” At the age of 57, Kitti started a job-training non-profit in Clarkston called Refuge Coffee Co.

(I could write an entirely separate story about this massive endeavor, but I’ll just let Kelly Clarkson tell you about it instead! 😳)

Kitti joked that her title at Refuge was Chief Excitement Officer, and in addition to fundraising and general leadership, she told the Refuge Coffee story through their social media and through their emails—which she still writes, now almost a decade later. Her writing became storytelling, which not only provided a job for Kitti but also for the dozens of refugees and immigrants Refuge has been able to hire since its inception.

Kitti became pretty well-known because of Refuge, with features on CNN, NBC Nightly News, and our girl Kelly Clarkson’s show. (I’ll never get over my mother-in-law sharing the couch with Jewel!) The press appeal was obvious—good work, good people—but I know so much of Refuge’s success came from Kitti’s ability to tell a story.

(I can promise you Kitti is cringing at this, as she’s always quick to attribute any of Refuge’s success to everyone else on the team. She jokes that she’s only a great Founder because she’s good at finding the right people!)

Over countless cups of coffee, Kitti found beauty in the lives and stories of her neighbors and created a place for others to do the same.

In the spring of 2023, her husband found himself back in the hospital with complications from congestive heart failure, which was a complication from radiation, which was a complication from cancer... We expected another simple procedure, but as the days progressed, Chief’s organs began to fail.

In what was the most brutal but holiest of moments, I watched as Kitti said goodbye to her husband of almost 45 years.

This mortal marriage.

It’s been almost two years since that moment, and in that time, Kitti has navigated unimaginable grief alongside a life that doesn’t allow her to fully stop and grieve. She still runs Refuge. She’s still a mother and a grandmother and a daughter and a friend. She still navigates the daily minutiae of eating and sleeping and existing.

And that existing has proved particularly tough. Just months after Chief’s death, Kitti was diagnosed with breast cancer. In the last year and half, she’s had a double mastectomy, a hip replacement, and a terrifying afib episode that landed her in the same hospital where she lost her husband.

A friend so poignantly said that after a lifetime of navigating Chief’s health battles, it’s as if Kitti’s body was waiting to have the space for her own.

For the first few weeks after Chief died, Kitti read all of his old letters and journals. She pored over his words, until later that spring, when she began to have a few new ones of her own.

She wrote and posted the following poem on Instagram:

One gift of this sorrow

is that it leaves no space for fear—

that forever lingering thing

that quietly consumed me,

that nibbled at the edges of

the joy that could have defined me.

It was not clean, honest, or noble.

Fear did nothing to prepare me

for the loss I feared most.

I justified being afraid

of the destination

I’ve arrived at now,

calling it pre-grief

(no such thing)

or, more falsely, love.

And now—

in this severe present tense—

sadness has swallowed

my interior whole

and leaves no room for the old fear,

for any fear at all.

It has moved into my soul

as a clean, honest, noble,

all-consuming guest.

I am not ashamed of it.

(Fear, I hid it, or

in clarifying moments,

called it

all the bad names

it deserved,

yet still refused to see it

for what it was.)

Grief is not the horror

fear most surely is,

and yet now I tremble,

as is right,

with the knowledge

that nowhere does the Holy Scripture

say “Jesus feared,”

but rather, “Jesus wept.”

And so, I’ll weep enough tears

to fill up the vast inner landscape

where fear once lived.

I’ll weep as a holy task,

one that tenderly draws me

into the sacred space

where my Lord has gone before

and where he is with me now.

Kitti Murray, May 2023

“Your words describe all the ingredients of grief so perfectly,” one comment read. “Sharing your journey helps so many others understand and allow for their own tears— which is so you. Thank you.”

Kitti has continued to write and share her poetry, calling it “a healthy, necessary expression right now”—something that’s helped her understand her excruciating feelings and find some sense of clarity and hope. In them, she’s wrestled with anger, honored her memories, and even defended her short hair.

I cry every time I read one.

Friends encouraged her to compile a book of her poems, but she waved that off. “Who wants a book of sad poetry?”

But then, maybe just as an excuse to stop and grieve, she began to write a story with Chief, taking bits of his journals and letters and intertwining them with her poetry.

Her writing friend Ben read through the first few chapters. “This isn’t a story about grief,” he told her. “This is a story about love.”

I’ve read through the first few chapters too, and it’s true; they say grief is the other side of love’s coin, that it only exists where love lived first. The words, even the sad ones, point towards a deeper understanding and appreciation of love.

It would be easy for Kitti to create a timeline and checklist and proposal and plan for this book, but I admire how she’s approached it.

She writes when she has something she needs to understand.

She’s heading in the general direction of a book, but she’s open-handed with it. “Right now the process nor the outcome matter to me,” she said. “Plus, there’s nothing remarkable about our story.”

In the piece I wrote after Chief died, I said, “The unique role of the daughter-in-law is bearing witness to the inner workings of a family, for better or worse. We are an outsider, deeply embedded.”

With this in mind, I got to raise an eyebrow at Kitti when she made the “unremarkable” comment—and she knew what I meant. For two decades, I’ve borne witness to their inner workings, and I can say that the most remarkable thing about their story is the mundane, unremarkable, mortality of it all.

Perhaps it was “the gift” of that early cancer diagnosis, or of the countless health scares that followed, but Chief and Kitti did not need a specific outcome nor storyline to validate their love. They got to experience and appreciate it daily, as it happened.

“It was not remarkable,” Kitti then said in response to my eyebrow, and then she conceded. “But it was beautiful.”

It is this reverence and honor that Kitti has brought to every story she tells—from the books in which she has collaborated to the “more beautiful refugee story” she gets to tell at Refuge.

And now, through a grieving heart and the love at its core, she gets to honor her own story.

Which is remarkable, even in the eyes of the daughter-in-law.

-Callie

🪩 Meet Your Fellow Email Subscribers 🪩

Sam Rauschenberg, the VP of Organizational Effectiveness for Achieve Atlanta, who also writes an email series called Southbound. As a 10th generation Southerner, he explores overlooked stories of the South and wrestles with how they affect us today.

Sarah Donjon, founder of JJ’s Flower Shop. What started as a “build-your-own-bouquet” flower truck has since grown into a brick-and-mortar shop and an online biz with national shipping. And it’s all just so beautiful!

Next time, Kitti and I will share a primer about fundraising, a task she swears she hates (but I think she’s quite good at). Stay tuned!

What is this email?!

I’m Callie Murray, a self-proclaimed Project Person. From a fake wedding company to a mountain shack to a novel, I’m always up to something.

I send an email like this every other Friday, alternating between a profile I’ve written about a fellow Project Person or a primer I’ve compiled with tips & tricks for your own entrepreneurial adventure.

Know a Project Person who should read this? Forward this email!

Are you building a business, side gig, or passion project? Subscribe below!

And please feel free to respond with any comments or ideas. I read every email, and your support means the world.